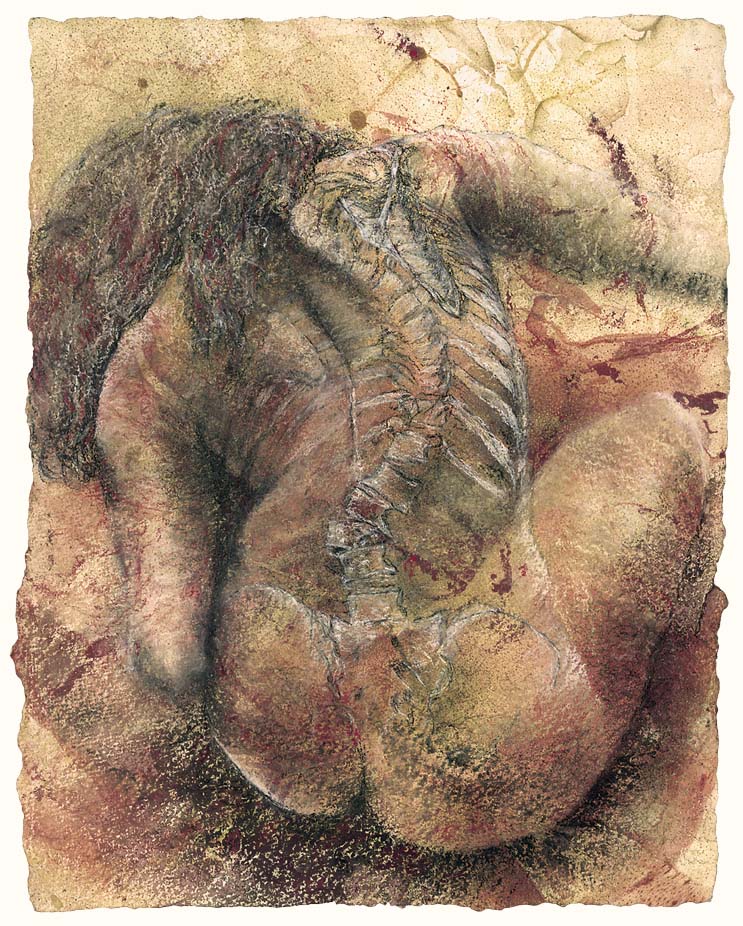

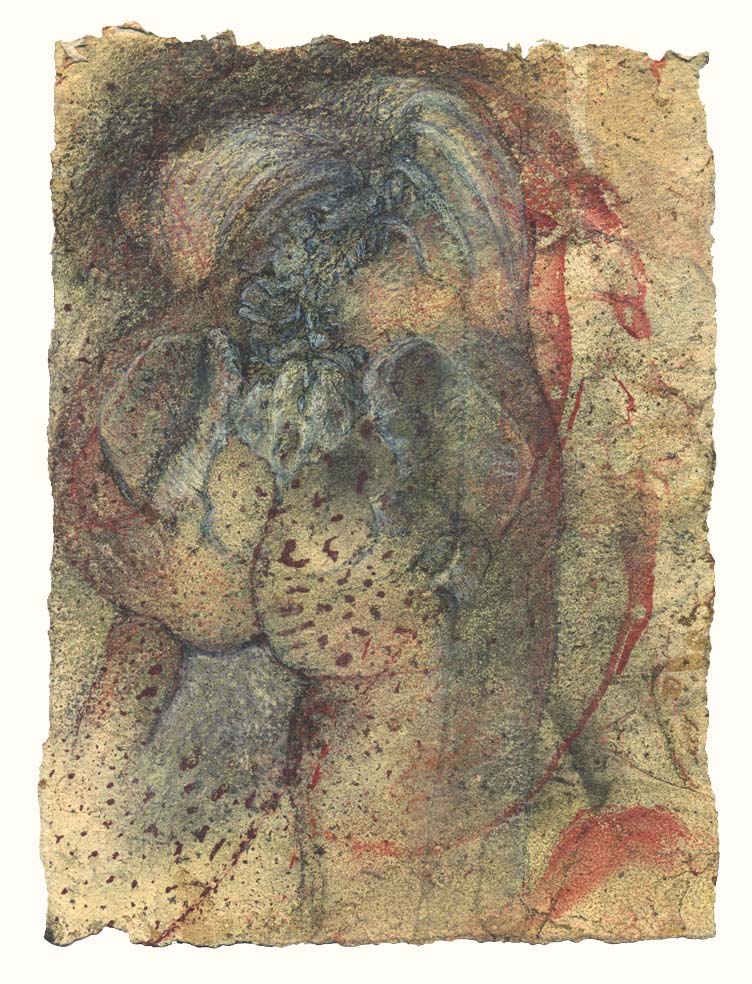

With its complicated rotational dynamics, scoliosis is fundamentally visual – all about spatial relationships, asymmetry, and balance – which makes it a great subject for art. Drawing myself, I could work from the inside out, tuning in to sensory and kinesthetic perceptions and finding beauty in a curving spine.

Anatomy-based movement practices made me feel more whole and three-dimensional, and brought me into closer connection to my inner body. I found myself fascinated by the intricate beauty of the human skeleton.

Spinal surgery and a year in a full-body plaster cast, at age thirteen, had been a life-defining experience. Later, as the uneven pressure of gravity bore down on my vulnerable spine, making art became a compelling need. I embarked on an artistic investigation of my own body and its unusual anatomy – a quest that has engaged me ever since.

Scroll down or click here to read The story behind the art

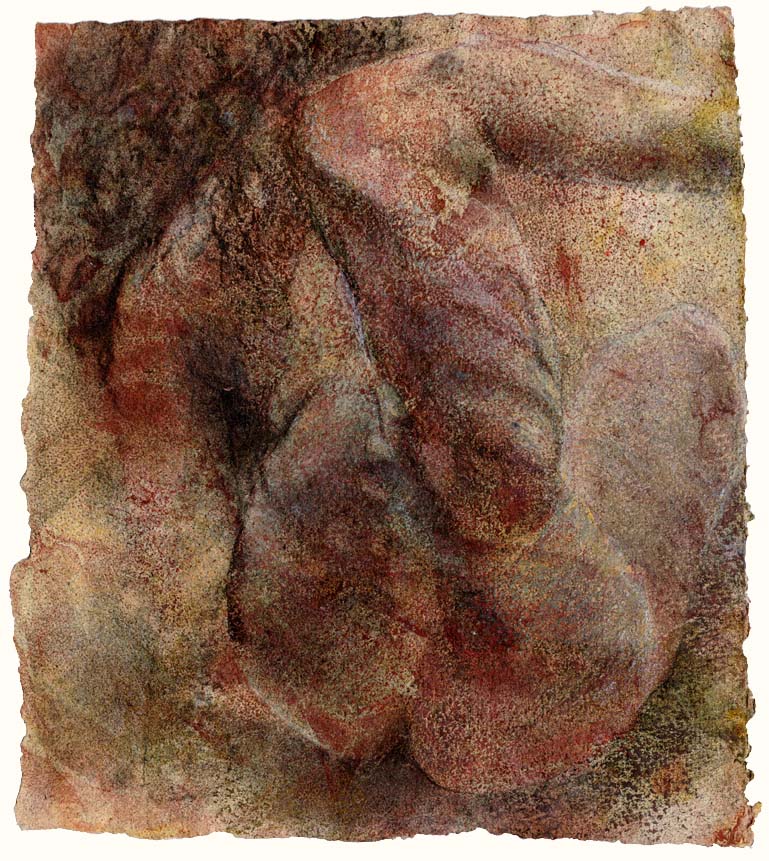

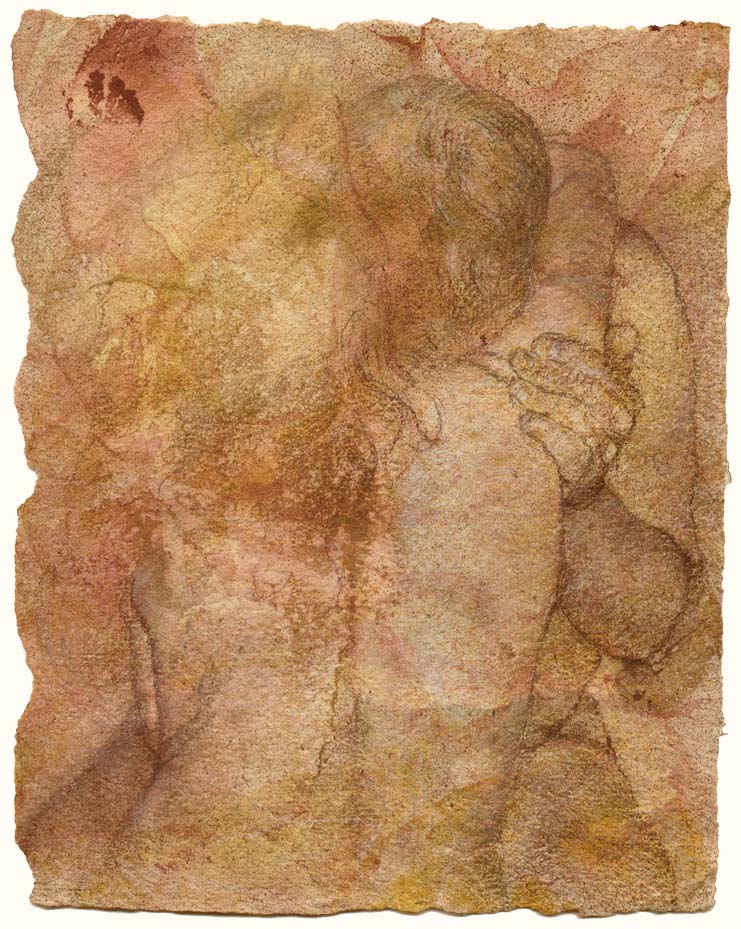

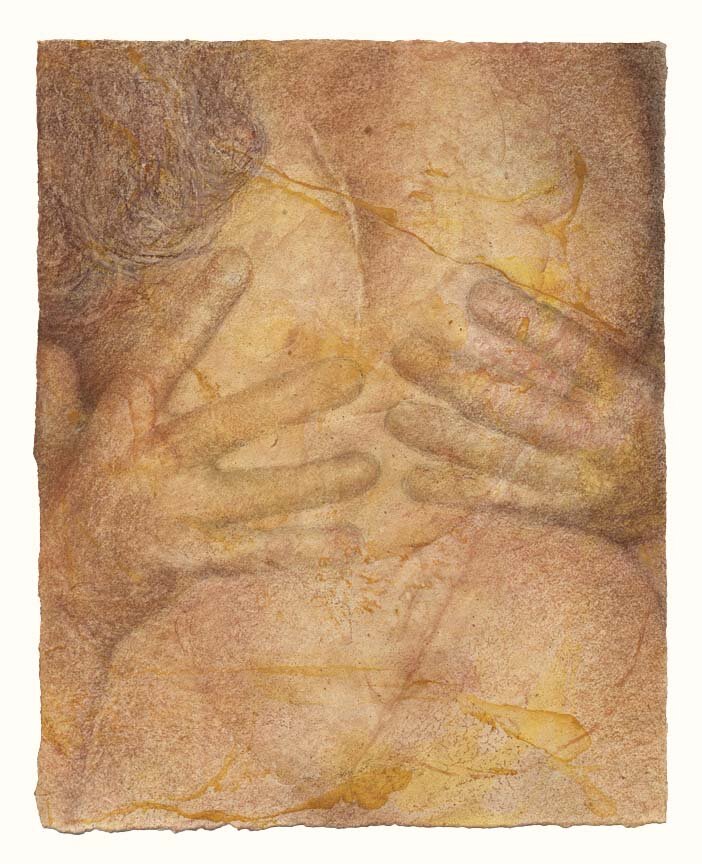

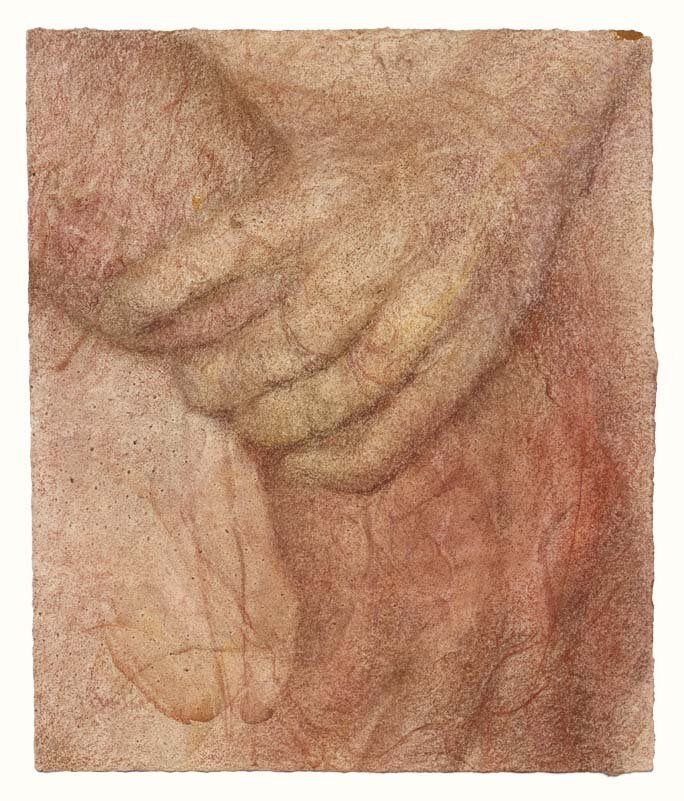

Drawing myself with my skeleton visible, in a lover’s embrace, felt healing: an acceptance from the person whose body I felt closest to. And the hands also signaled a growing reconciliation with those who had touched and gazed: the doctors who hurt me as they tried to heal me.

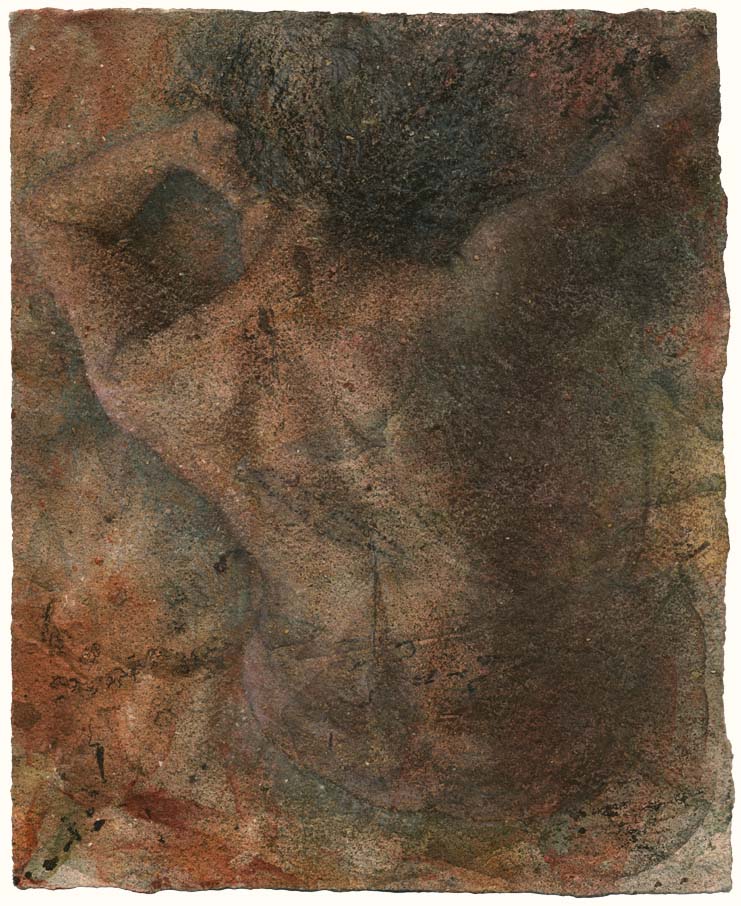

Drawing keeps me connected to my sensual self. When I make new drawings of my figure in poses from years ago, my present reality is overlaid with sense memories of earlier times.

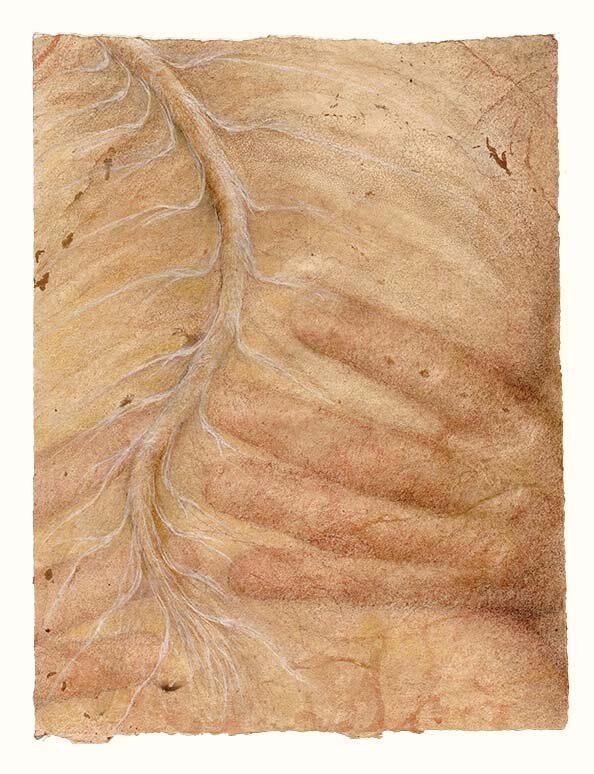

I feel attuned to my “body-self neuromatrix” – the network of sensory and proprioceptive signals that give us “the experience of ‘owning’ our own body … a link between anatomy and experience.”

[the body-self neuromatrix as described in Ariel Glucklich’s book Sacred Pain]

The story behind the art

My spinal curvature was diagnosed in childhood, and I had to have surgery, and live for a year in a full-body plaster cast, when I was thirteen. This was a life-defining experience, of constriction, repression, many hard things. It also deepened my sense of empathy and made me aware of how much is hidden under the surface of the selves we present to the world.

Over the next twenty years, the uneven pressures of gravity bore down on my vulnerable spine and constricted rib cage, and eventually brought pain and disability into my life.

In an aha moment in the early 1990s, an idea came to me: to conduct an in-depth artistic investigation of my own body and its unusual anatomy.

With all its limitations, my body was still limber and flexible, expressive and attuned to interesting relationships with space, light, another body. Through my work with anatomy-based movement practitioners, especially master dance anatomist Irene Dowd, I became more aware of my proprioceptive, inner body sensors and signals, and more centered and balanced in my body. We began drawing together from Irene’s real human skeleton, and I found myself fascinated by the intricate beauty of bones.

Translating my inner body awareness into drawing, I could create visual images in space the way a dancer uses choreography … evoking a consciousness of the body that often remains below the level of articulated thought.

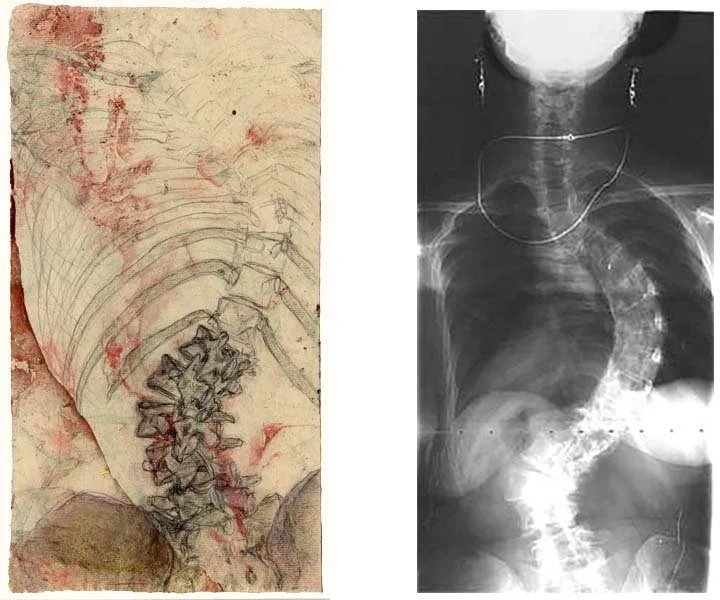

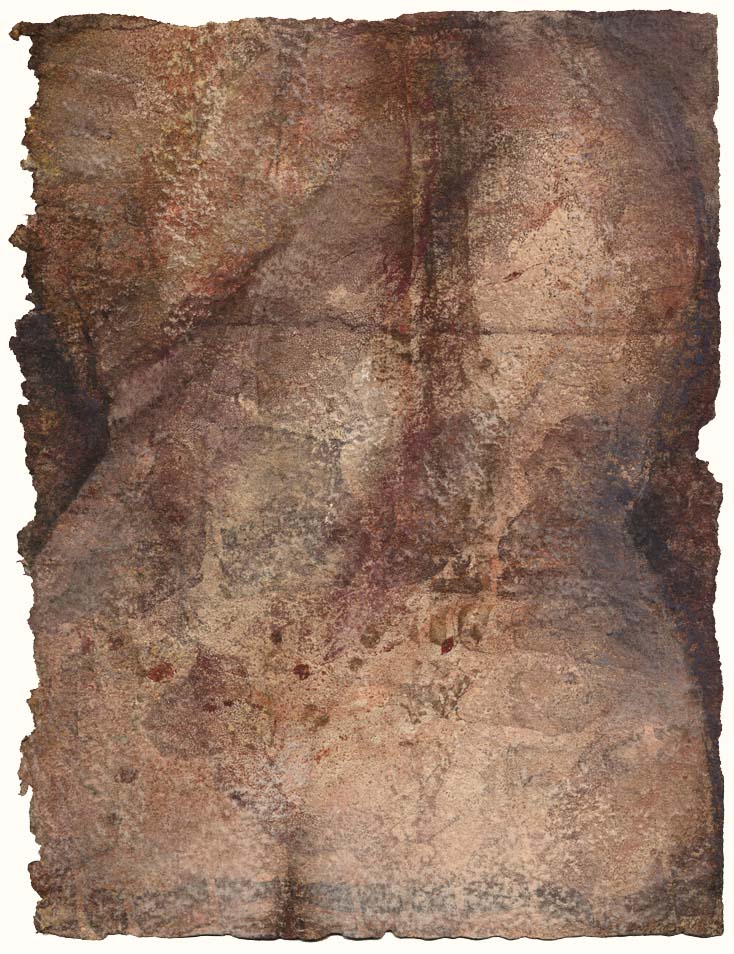

Over a lifetime of x-rays, I had always been intrigued by these shadowy, mysterious pictures of my own inner body – but they seemed to belong more to the doctors than to me. Putting my x-rays up on my own lightbox, and converting their flattened, black-and-white shapes back into three-dimensionality, I began to feel whole again. It was powerful to draw my scar, my deformity – giving myself permission to explore territory I had long kept private, and to some extent even hidden from myself.

I began to collaborate with orthopedic surgeons and radiologists to have medical images made for the purpose of art. It was exciting to art-direct my first x-ray! Keeping my earrings and necklace on (instead of being made to take off everything metal, as usually happens) made me feel triumphant, and made the x-ray image more personal. Working with doctors as an artist and fellow professional, I felt respected and seen in a way I never had as a patient.

Soon I was searching for a more three-dimensional medical imaging technology, and in 2000, thanks to Dr. Andrew Litt at NYU School of Medicine, I was able to have a cutting-edge spiral CT scan with 3D volume rendering. It was a stunning experience to see my skeleton appear in 3D on a computer screen, after all the years I had spent trying to visualize it. In 2008, when the technology could capture an even greater level of detail, I had a second spiral CT scan. I’ve been using those scan images ever since to inform my visual explorations of my inner spaces.

I drew my figure from the outside first, in poses that came from my own vocabulary of movement. Then I made studies of the skeleton in that pose, using my 3D scan films and the human skeleton as references. Once I had come to know the pose from inside and out, I put the elements together in a drawing that made the skeleton visible through the transparent surface of the skin.

More about the drawings: media, paper, etc.

Overview of all the artwork